A 2024 Midyear Outlook

With the midpoint of 2024 here, we are taking a look back at the start of the year while simultaneously looking ahead to what’s on the horizon. Over the next few weeks, we will be offering fresh insights into the economic and market landscape. This includes important topics such as the economy, the stock market, the bond market, geopolitics, the election, and more.

This week, we kick things off with an economy review.

We Have a Delayed Landing, But Still a Landing

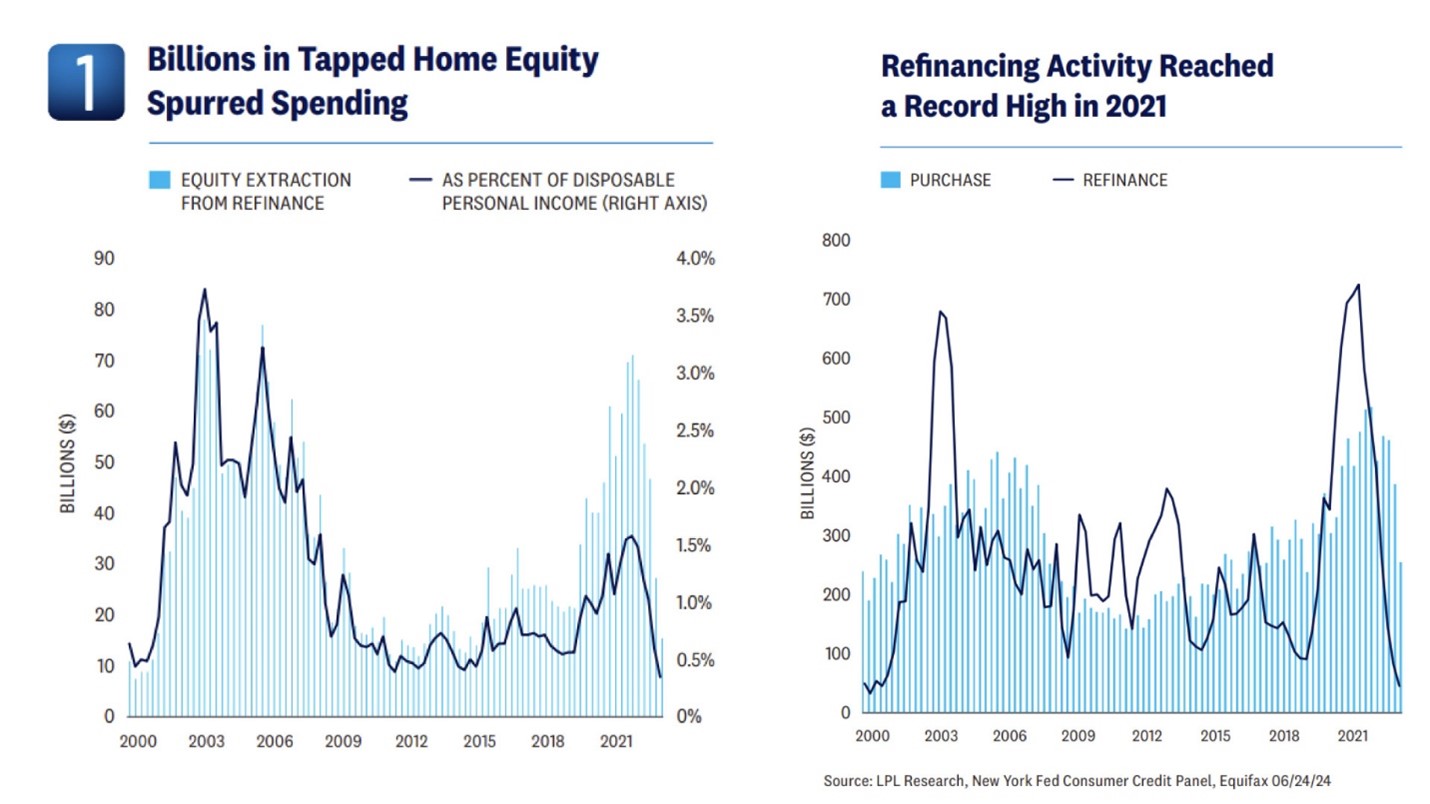

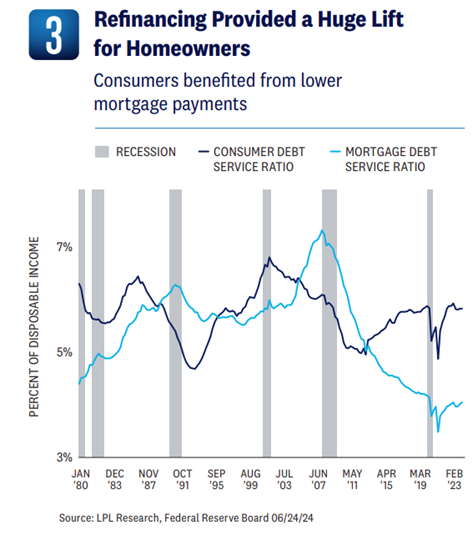

Recent data on refinancing activity provides a clue on why the economy has experienced a delayed landing. The housing market often explains a lot of what is happening in other sectors of the economy, and this time is no different. Roughly one-third of mortgages were refinanced in the quarters following the pandemic recession of 2020.¹ And because of 2020’s extremely low mortgage rates, these homeowners lowered their monthly payments, thereby increasing their disposable income. Other homeowners took advantage of healthy home equity and took cash out to support more spending. The incredible impact of such historic refinancing activity caught many, including us, by surprise. In addition to the oft-mentioned excess savings from stimulus and temporarily curtailed spending, improved household financial conditions from low mortgage rates kept the economy out of the doldrums.

As we look ahead, however, the domestic economy looks to be late cycle, and recent data suggests the consumer has started to slow down. We indeed expect the consumer will slow spending later this year as data from both the Conference Board and the University of Michigan revealed that most consumers have pivoted away from big-ticket buying plans. These changes in buying plans could have knock-on effects in other categories of spending. Investors should anticipate a forthcoming downshift in consumer activity [Fig 1].

A Less Rate-Sensitive Economy Causing Some of the Delays

One of the Fed’s monetary tools involves setting the federal funds rate, an interest rate that influences other market rates such as bank loans, CD rates, and mortgage rates. Typically, higher rates will slow the economy and release some of the pressure on consumer prices. But that hasn’t happened, at least not uniformly across the economy nor at the same magnitude as previous years. One of the important things investors learned from the first quarter GDP report was the economy is less sensitive to interest rates in this cycle. Despite high interest rates and residential investment, a traditionally rate-sensitive sector contributed a respectable amount to growth in the first quarter. Of course, the dearth of housing supply drove construction activity in the first quarter, which more than offset the headwinds from higher interest rates.

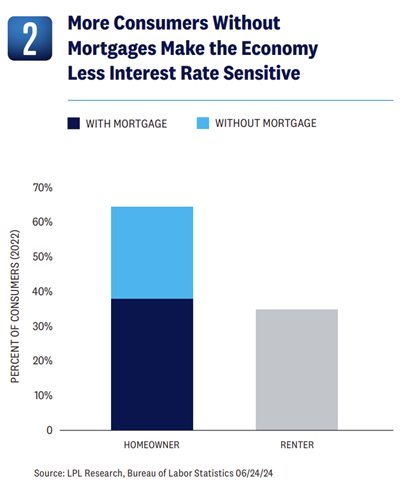

Meanwhile, the Fed is backed a little bit into a corner as some sectors of the economy appear more immune to higher interest rates than others. At this rate, we expect the Fed to stay on hold longer than they would in a normal cycle, which increases the odds of either stagflation or a bumpy landing. Some consequences of unusually low mortgage rates are a short supply of homes on the market and homebuilders needing to play catchup in an economy that overall is less rate-sensitive than ever before [Fig 2].

In a less rate-sensitive environment, tighter Fed monetary policy (higher interest rates) has a weaker effect on the economy because of the increasing share of homeowners who have no mortgage or a low fixed rate mortgage.

Notably, the Federal Housing Finance Agency revealed that roughly half of all mortgages have an interest rate below 4%. As millions of Americans took advantage of low rates, homeowners have historically low debt service payments as a percentage of their disposable income [Fig 3]. The New York Fed estimates that mortgagees gained an average of roughly $220 per month from refinancing. This extra cash was added to the post-COVID-19 consumer spending splurge and has delayed the inevitable weakening of economic conditions.

Optimistic on Inflation’s Trajectory, But Headline Data May Lag

We can say unequivocally that services inflation is past its peak. After an unusual spike in January, the monthly pace of services inflation slowed down to its lowest since November of last year. This trend will continue, although probably not enough for inflation to reach the Fed’s long-run target of 2% by year’s end. Core services inflation is important to watch because it reflects underlying price pressures that are less volatile than food and energy and can give a clearer picture of longer-term inflation trends. Investors should expect core services inflation to cool as labor costs decelerate.

The real problem for the Fed is that it could take some time for changes in labor costs to impact broader consumer pricing, and markets are getting increasingly frustrated with the Fed’s decision-making process. In recent years, governments have increased wages faster than the private sector to attract workers and fill open positions, but we should focus on the private sector since that is what drives business activity. The Fed will not likely begin cutting rates until they have more confirmation that consumer prices are easing, but as far as we are concerned, that is a matter of “when,” not “if”.

Labor Demand is Key to Forecasts

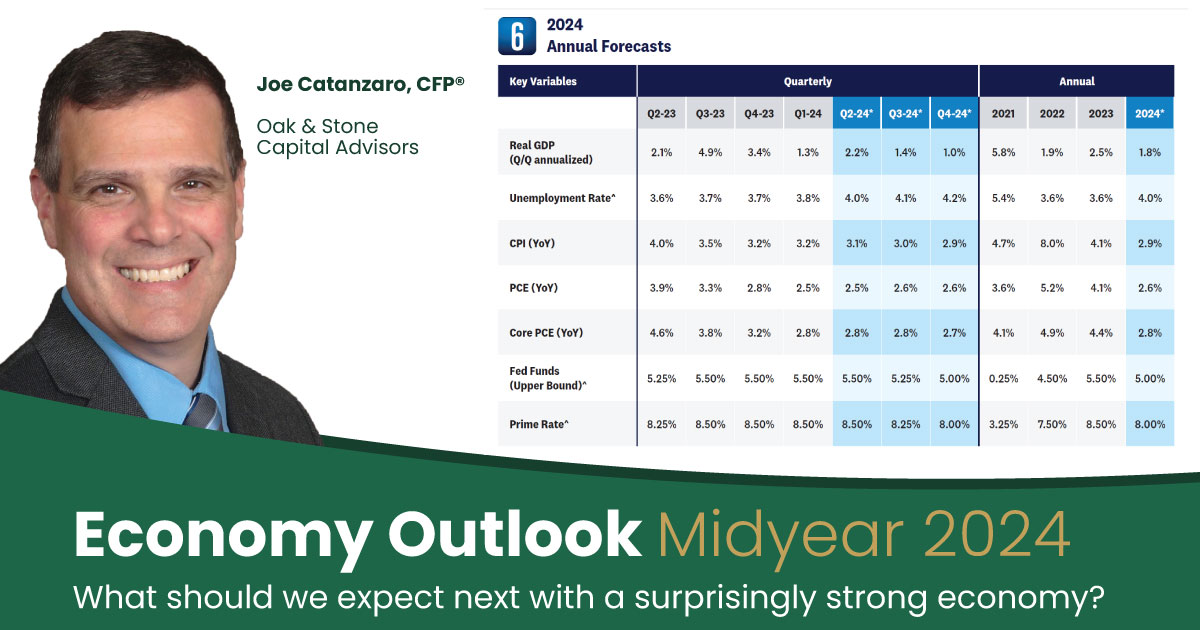

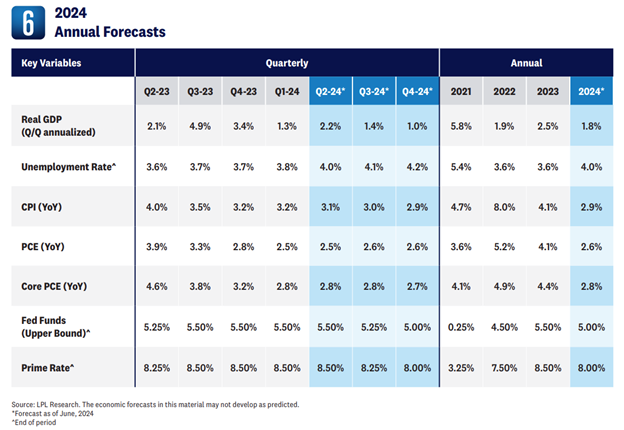

The economy will likely downshift in the latter half of 2024, as consumer spending slows from the breakneck speed of 2023. Some weakening in the labor market is expected to contribute to the economic downshift as well. The quits rate (the percentage of employees voluntarily leaving their jobs) fell as workers have become less inclined to switch jobs and the average workweek for private payrolls has declined, suggesting weaker labor demand. The unemployment rate will stay historically low but should inch up in the second half of the year. The slowing demand for labor will eventually ease inflation pressures, giving the Fed some leeway to cut rates later this year. The evidence of slower payroll growth and fewer hours worked we have witnessed imply the economy will slow at a measured pace, barring any exogenous shock [Fig 6].

THE BOTTOM LINE:

The surprisingly strong economy, fueled by high-income consumer spending and uneven interest rate sensitivity, is finally showing signs of stalling out. Expect slower spending, a softening labor market, and the beginnings of a measured economic slowdown in the latter half of 2024.

While inflation may take some time to fully ease, the Fed will likely have room to cut rates before the end of the year as the weakening economic picture becomes more apparent.